What is new in the AR6 WGII report since the fifth assessment report?

There has been tremendous development since the IPCC fifth assessment report. The most crucial part is the interlinkages between climate, human society and ecosystems including biodiversity. It is central because it highlights the extent of climate change impacts and risks on humans, ecosystems, and biodiversity. This is the most important framing because it lends climate risks to possible solutions such as adaptation and mitigation.

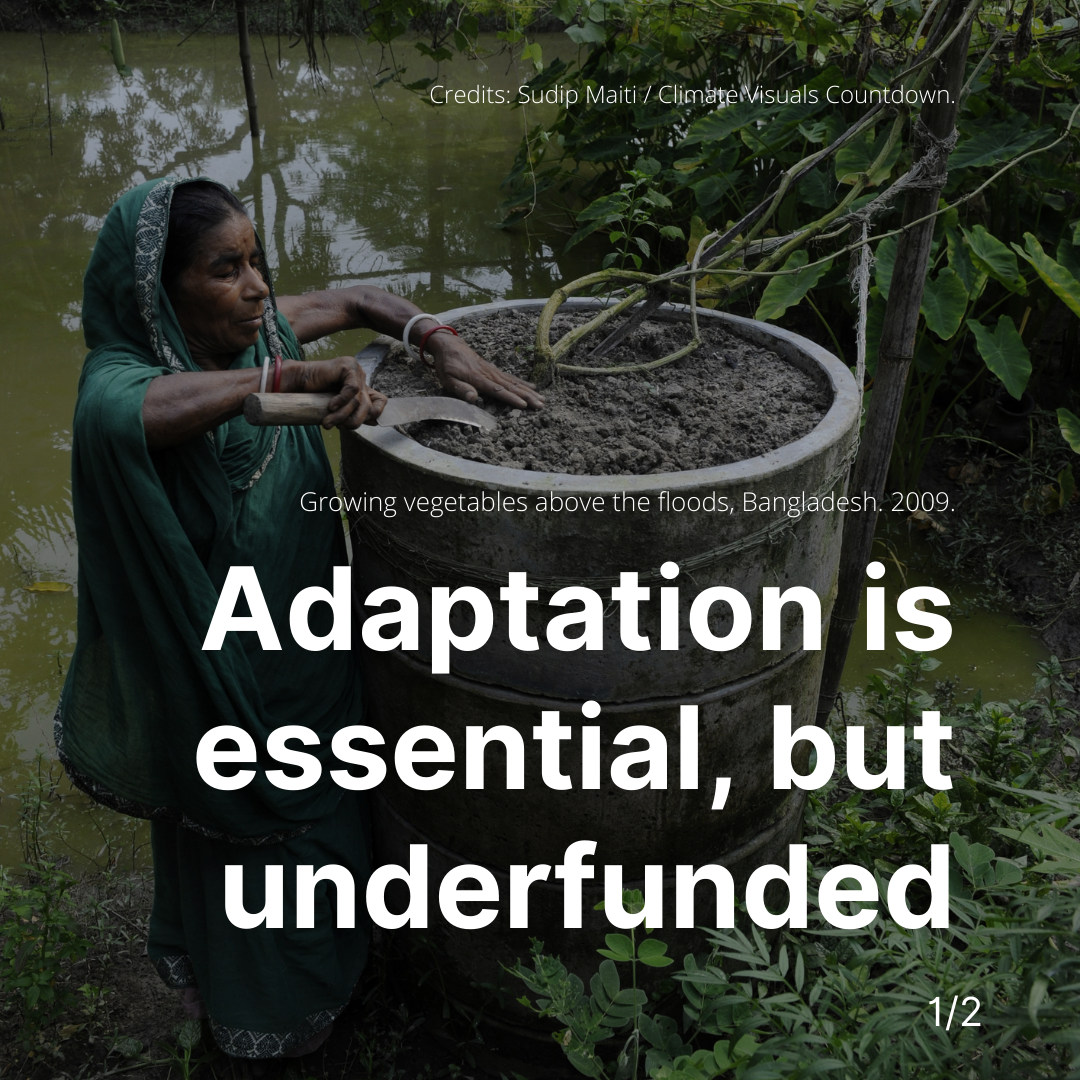

The IPCC Climate Report is calling for transformative adaptation action which means we don't have the luxury of adapting incrementally or sequentially. The window of opportunity to act exists but is narrowing and we need unprecedented changes in all systems, scales and sectors. To enable this transformative action, the report discusses multiple 'enablers' from adequate and targeted finance, flexible and forward-looking decision-making, institutional capacity (to make decisions under uncertainty), and critically behavioural change.

Climate change will hit India’s people, agriculture and infrastructure

India is one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate-induced flooding, heat stress and droughts, according to the new IPCC WG2 report on impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. India is exposed to many flood hazards, from sea level rise, rivers and melting glaciers.

Major floods and landslides killed over 700 people and caused USD 11 billion worth of damage in India over the course of 2018 and 2019. The WG2 report found that the city of Mumbai is the second most exposed megacity to coastal flooding as a result of sea-level rise. Without climate mitigation, the city could suffer economic damages of USD 49-50 billion by 2050 (cumulatively) from coastal flooding alone (chapter 10.4.6.3.4). The report also found that India has the world’s second-highest exposure to flooding rivers, which could amount to an annual average loss of USD 6 billion (chapter 10.4.5.3.6). Melting glaciers in north India also cause outburst floods, which threaten the security of western Himalayan communities. As an example, a flash flood triggered by a glacier lake outburst in 2013 caused devastating floods and landslides, killing over 5,000 people in the state of Uttarakhand.

Extreme heat is among the most deadly and costly climate hazards. Globally it claimed 166,000 lives between 1998 and 2017, a third of which can be attributed directly to climate change. Projections show that unabated climate change is likely to cause wet-bulb temperatures, which are a measure of heat stress, to approach or exceed survivable limits over much of India by the end of the century. Critically, projected higher temperatures will increase heat-related morbidity and mortality. Heat stress was also found to be the dominant cause of GDP loss for India if warming continued to 3°C.

The WG2 report found that droughts and water stress are expected to increase across Asia as a result of climate change, and this could have serious repercussions for food security and civil conflicts. The agriculture sector, which makes up about 16.5% of India’s USD 2 trillion economy and employs more than half of the country’s 1.3 billion people, is particularly vulnerable to drought. An increase in drought conditions will severely impact India’s overall economic growth given its importance to the economy (chapter, 10.5.4.3).

India will face severe economic damage without emission cuts

India's GDP per capita is already 16% lower than it would have been without human-caused warming since 1991, according to a study cited by the IPCC report [Ch 16, p.22]. India is the country that is economically harmed the most by climate change, with every tonne of carbon dioxide emitted globally costing the country around $86, according to a separate study cited by the report.

Six hundred million people in India already face acute water shortages, according to government think tank Niti Aayog. The WG2 report found that higher emissions will heighten the drought risk for urban populations in megacities Delhi and Kolkata, which are already experiencing water stress.

IPCC's latest report calls for a pronounced focus on stepping up climate risk insurance

In 2020-21, the maximum number of insurance claims out of the total in India were due to damages caused by Cyclone Amphan, which caused immense damage in Eastern India including West Bengal. Yet India has the lowest rate of insurance penetration across Asia. The insurance sector is evidently ill-prepared for short-term and immediate climate-related risks, while we're not even discussing how to deal with multi-decadal changes like sea-level rise, heat mapping, drought etc, which is no longer a distant risk, but staring at us within 3-8 decades.

In general, insurers have long relied on ‘catastrophic models’, which use historical loss data to price future risks. However, unprecedented climate conditions have made modelling future losses more difficult than ever before. The potential for major events to overwhelm an insurer’s capacity to absorb climate-related losses is very real. For example, in 2018, the Merced Property & Casualty Company was unable to pay out all claims due to the wildfires in California and as a direct result was pushed into insolvency.

Increasing physical risks present challenges, both to market-based risk transfer mechanisms and to the underlying assumptions behind Indian insurers’ business models. The ability to reprice insurance premiums on an annual basis is the industry’s main tool in mitigating financial losses. However, continuous premium hikes are not a sustainable, long term solution for the industry, as spiralling premiums are likely to lead to an availability and affordability crisis for consumers.

The ability of insurers to articulate their management of climate risk is not only important to their shareholders, but also to the financial stability of the economy. This is why European regulators are fine-tuning their approach to climate stress tests.