Impacts of Climate Change on Agriculture in India: Study (Part 1)

Deep-dive into how the changing climate has impacted agriculture and food production in India

By Editorial Desk / Dec 20, 2023

The summer monsoon season is the main agricultural season in India, with much of the central and western regions receiving more than 90% of annual rainfall during this period, and the southern and northwestern regions receiving 50-75%. Around 50% of India’s crop cultivation area is rainfed, making it particularly vulnerable to climate impacts. Agriculture is highly dependent on reliable, consistent and timely rainfall during the monsoon season, and any variability can have severe consequences.

How has the climate of India changed over the last century?

Though monsoon rainfall is a naturally highly variable phenomenon, evidence suggests that summer monsoon rainfall has declined by 6% since the 1950s, with decreased rainfall particularly evident in the Indo-Gangetic Plains and the Western Ghats. In the central region of India, where about 60% of agriculture is rainfed, summer monsoon rains have declined by 10%. While the monsoon rains have weakened, the intensity of the rains has increased, triggering dangerous floods. Studies attribute the changes to the warming of the Indian Ocean due to a combination of climate change, land-use change, and increased human-caused pollutants in the atmosphere. In the past half-century, extreme rainfall events over India almost doubled, while in central India, they increased threefold. As monsoons have become increasingly erratic, the weather is becoming more challenging to forecast. Changes to El Niño events may have also contributed to the changes to the monsoon (see here for an explainer on the impacts of El Niño).

India has warmed by at least 0.7°C on average since 1901. This warming - particularly since 1956 - is largely due to human-caused climate change and has been offset partly by human-caused pollution and land-use change. The average, minimum and maximum temperatures in India increased by 0.15°C, 0.15°C and 0.13°C, respectively, per decade from 1986 through 2015. Similarly, warm extremes have become more frequent in India since the 1950s, and particularly since the 1980s. This warming is uneven across India: it has been greater in the northern and central regions but weaker in the southern region.

The number of extremely hot days in India is persistently increasing due to climate change, particularly in inland areas. Records show that the number of extremely hot days has increased from 413 days over the 1981-1990 period, to 600 over the 2011-2020 period. A 2023 study found that 90% of India is at high risk of being impacted by climate change-induced heatwaves, with implications for food security and reaching sustainable development goals (SDGs). Human-caused warming is accelerating ice loss in the Himalayas, with significant implications for farmers who rely on the meltwater.

SNAPSHOT OF INDIAN AGRICULTURAL PRODUCTION

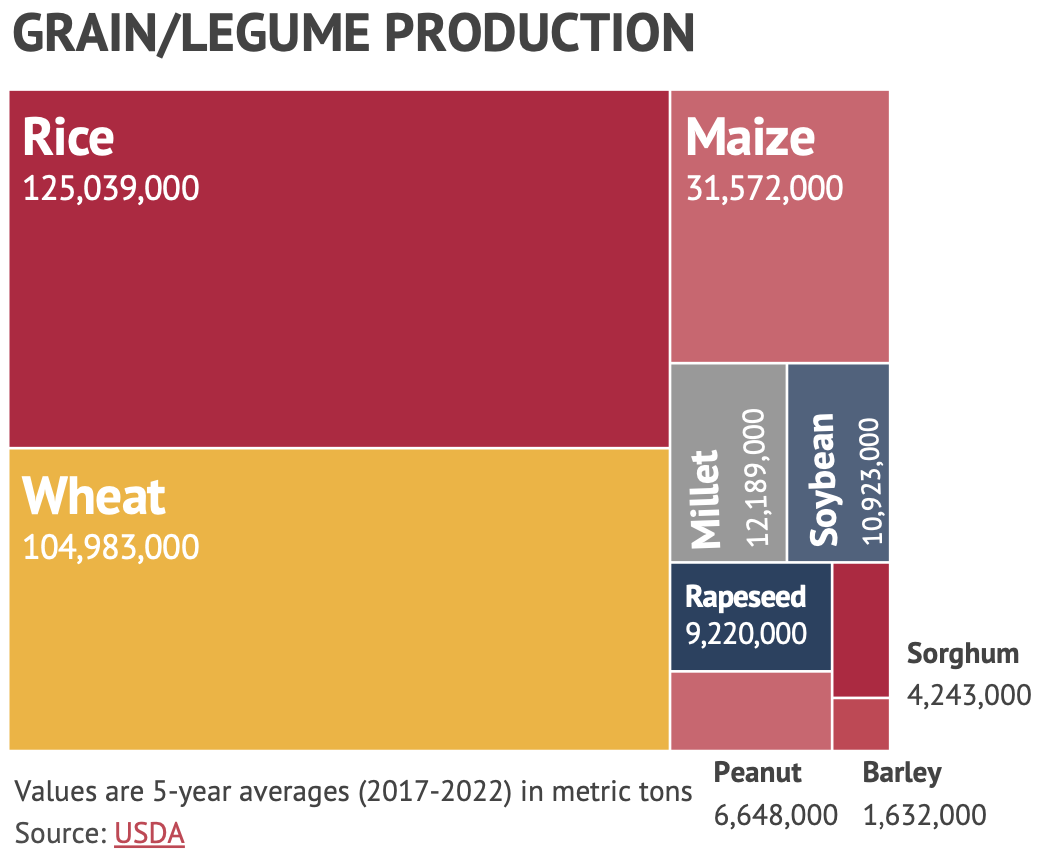

India is the world’s largest producer of milk, pulses, ginger, okra, banana, mango and the second-largest producer of fruit, vegetables, onion, rice, wheat, sugarcane, peanut, vegetables, fruit and cotton. Rice occupies the biggest share of India's cereals export, accounting for 80% (in monetary terms) during 2022- 2023. However, compared to other kharif grains such as pearl millet, sorghum and maize, which respectively make up around 8%, 2.5% and 15% of the grain supply during this season, rice is substantially more sensitive to fluctuations in monsoon rainfall. It is suggested that India’s growing reliance on rice has increased its vulnerability to climate change-induced food insecurity. Diversifying kharif crops may help mitigate against this.

Rice-wheat systems - in which rice is primarily grown during the monsoon (kharif) season and wheat is grown during the winter (rabi) season - dominate in India, with wheat and rice making up around 85% of total annual grain production. During the kharif season, rice makes up three-quarters of the grain supply for domestic consumption. However, compared to other kharif grains such as pearl millet, sorghum and maize, which make up around 8%, 2.5% and 15% of the grain supply during this season, rice is substantially more sensitive to fluctuations in monsoon rainfall. It is suggested that India’s growing reliance on rice has increased its vulnerability to climate change-induced food insecurity. Diversifying kharif crops may help mitigate against this.

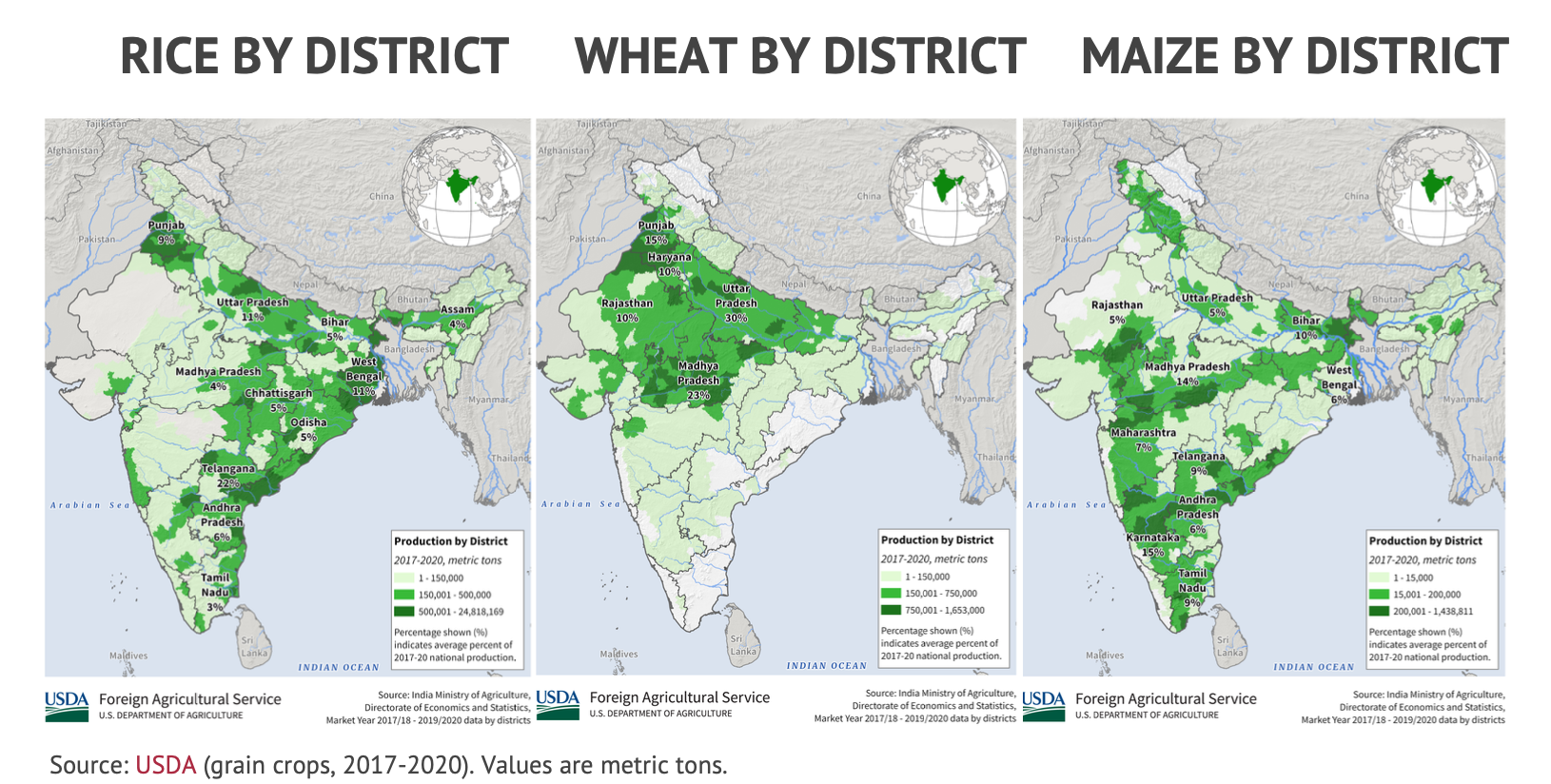

Shown are production statistics for three major grain crops by district (above) and four major perishable crops by region (below). For rice, Telangana (22%), Uttar Pradesh (11%), West Bengal (11%), Punjab (9%) and Andra Pradesh (6%) account for almost 60% of production. For wheat, Uttar Pradesh (30%), Madhya Pradesh (23%), Punjab (15%), Haryana (10%) and Rajasthan (10%) account for almost 90% of production. For maize, Karnataka (15%), Madhya Pradesh (14%), Bihar (10%), Telangana (9%) and Tamil Nadu (9%) account for almost 60% of production.

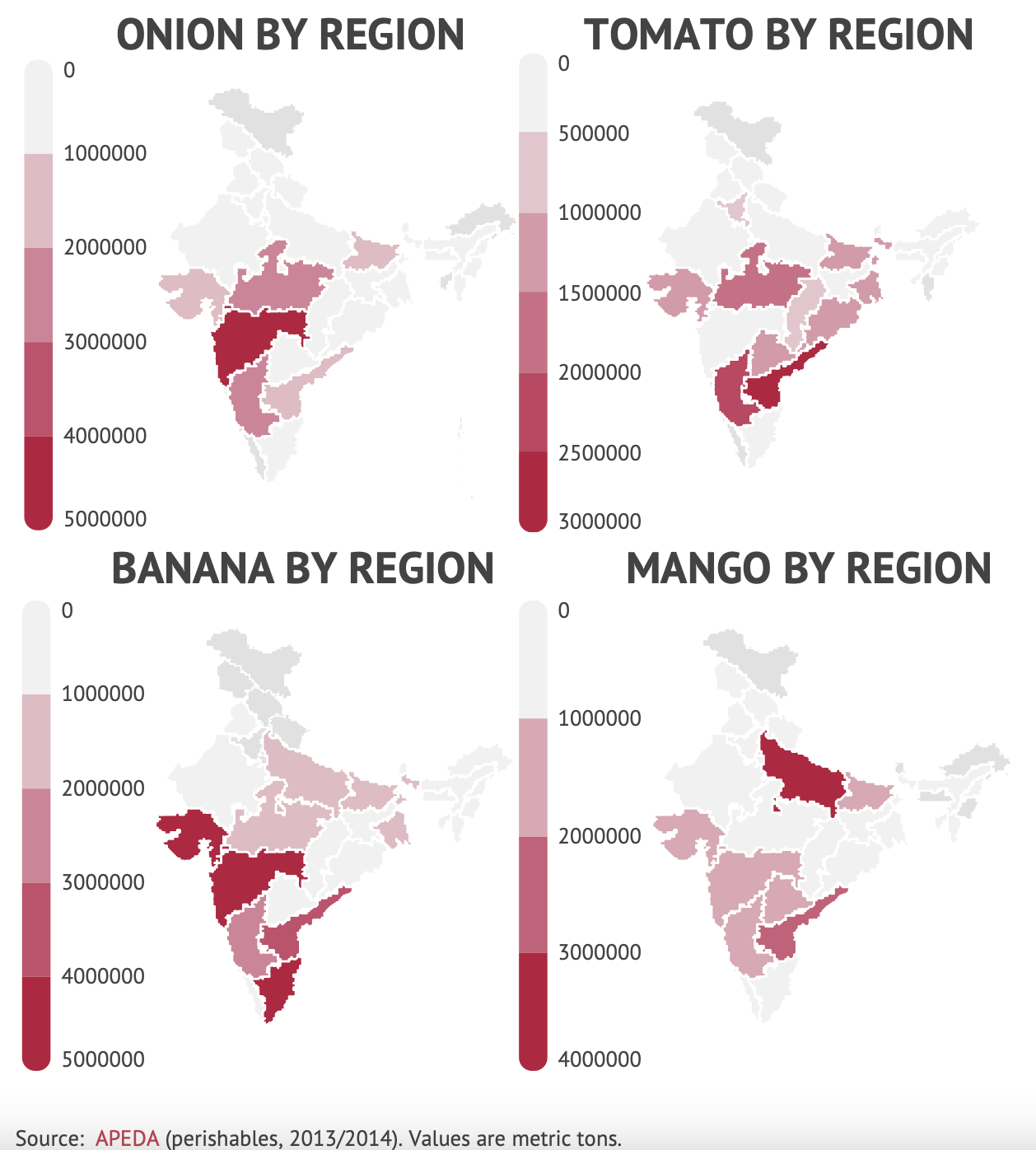

Tomato, onion and potato are the three most consumed vegetables in India. Banana and mango are important fruit crops in India, with mango accounting for around 57% of global production and banana accounting for about 25%. The bananas produced in India are almost entirely consumed locally. Maharashtra (30%), Madhya Pradesh (15%), Karnataka (11%), Gujarat (10%) and Bihar (7%) are the top fresh onion producers (top left), accounting for over 70% of production.

Andra Pradesh (18%), Karnataka (11%), Madhya Pradesh (10%), Telangana (8%) and Odisha (7%) are the top fresh tomato producers (top right), accounting for more than 50% of production. The top banana-producing states (including plantain) are Tamil Nadu (19%), Maharashtra (16%), Gujarat (14%), Andhra Pradesh (11%) and Karnataka (9%), accounting for around 70% of production. The top mango-producing states are Uttar Pradesh (23%), Andhra Pradesh (15%), Karnataka (10%), Telangana (9%) and Bihar (7%), accounting for more than 60% of production.

Regional Vulnerability to Climate Impacts

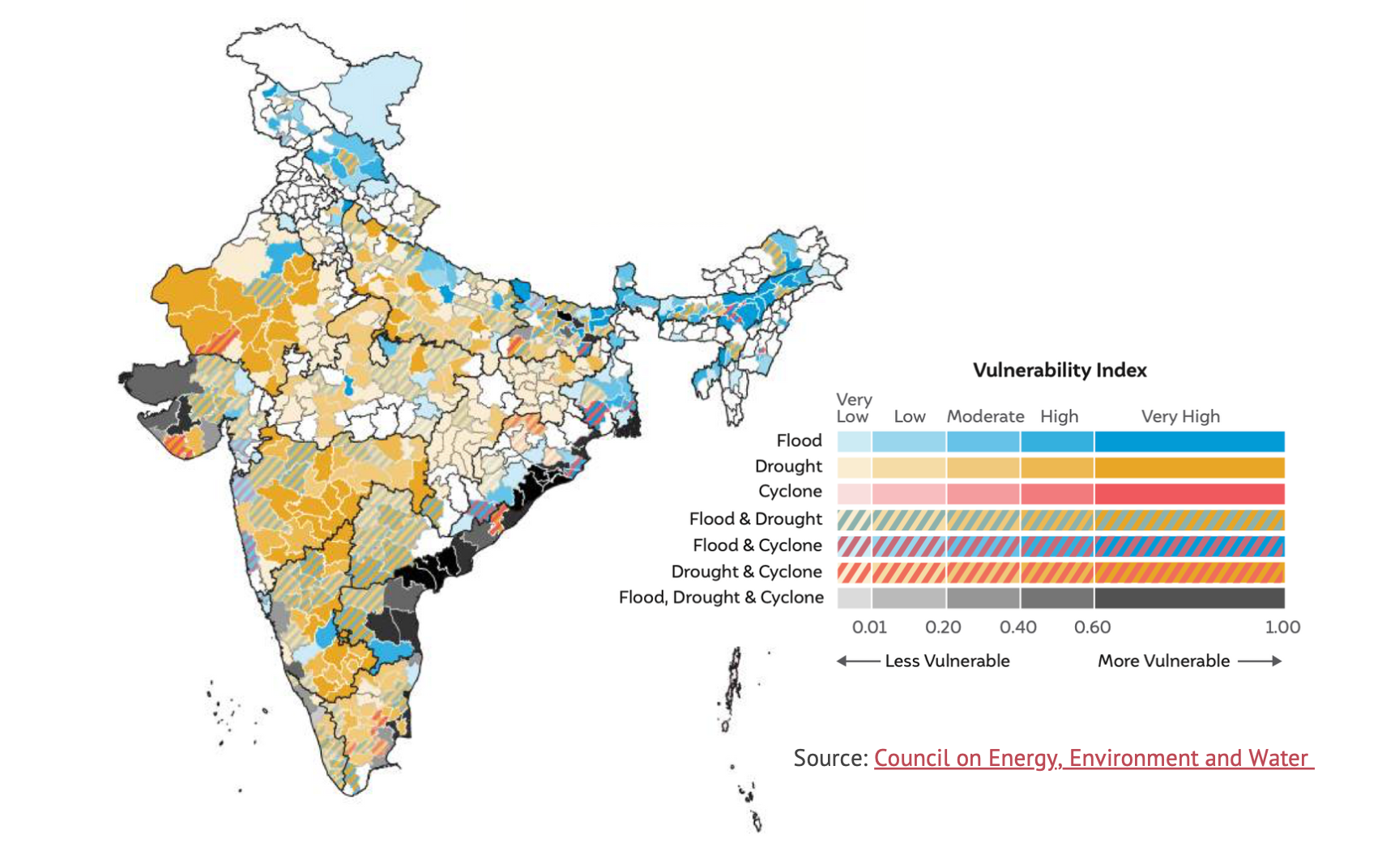

According to a report by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water, the southern and western regions of India are the most vulnerable to extreme drought, while the northern, eastern and central zones are moderately vulnerable, and the northeastern region is the least vulnerable. However, the northern and north-eastern regions are more vulnerable to extreme flooding. The eastern and southern regions are prone to a combination of droughts, floods and cyclones. The states of Punjab and Haryana, which produce around 50% of the national government’s rice supply and 85% of its wheat supply, are subject to extremely high water stress.

This is part 1 of the Climate Change and Agriculture series.

Climate Change Carbon Dioxide Emissions Developing nations Global Warming COP28