The many cascading effects unleashed by South Asia’s unprecedented heatwave season

Heatwaves in India and Pakistan this year were made 30 times more likely due to climate change, and are likely to become hotter and more intense in the coming years

By Editorial Team / Jun 7, 2022

Intense heatwaves wreaked havoc this summer season in India, with both March and April securing a rank each in the history of 122 years since the record-keeping began. Pakistan was no different, with several of its stations reporting day-time temperatures close to a scorching 50°C.

A study, led by World Weather Attribution, estimated at least 90 deaths across India and Pakistan on account of the 2022 heatwave. The report stated that human-induced climate change has increased the probability of an event like the one seen this year by a factor of about 30. Given the rise in average background temperatures in South Asia, a similar event would have been about 1°C cooler in a pre-industrial climate. The WWA study relied on six multi-model ensembles from climate modelling experiments using very different framings: Sea Surface Temperature (SST) driven global circulation high-resolution models, coupled global circulation models and regional climate models.

With the further rise in global mean temperatures, heatwaves are likely to further increase in terms of frequency and intensity in the coming years. In the scenario of global mean temperature reaching 2°C or more, such a heatwave would be more likely by an additional factor of 2-20 and 0.5°C-1.5°C hotter compared to 2022.

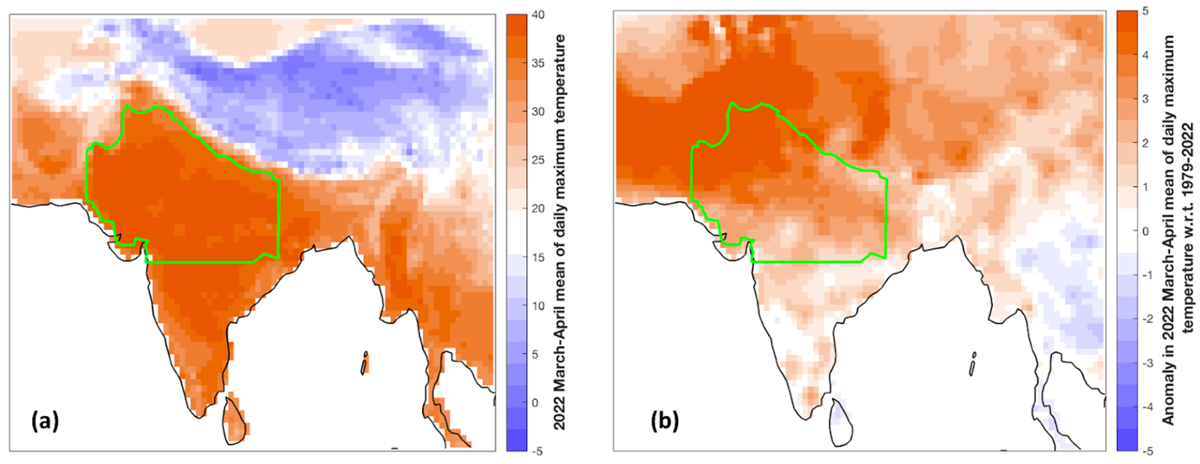

Figure 1: (a) March-April average daily maximum temperature for the year 2022 as observed in the CPC dataset. The study region is highlighted by the green polygon. (b) same as (a) for anomalies w.rt. 1979-2022.

Another study on heatwave, led by UK Met Office, climate change has made the chances of a record-breaking heatwave in north-west India and Pakistan more likely by over 100 times. Years with April-May temperatures higher than the one in 2010 are now common (return time of about 3 years) and. The threshold is set to be crossed almost every year by the end of the century. The analysis suggested that human influence has increased the likelihood of extreme April-May temperature anomalies by a factor of about 100. By the end of the century the likelihood is estimated to increase by a factor of 275 relative to the natural climate.

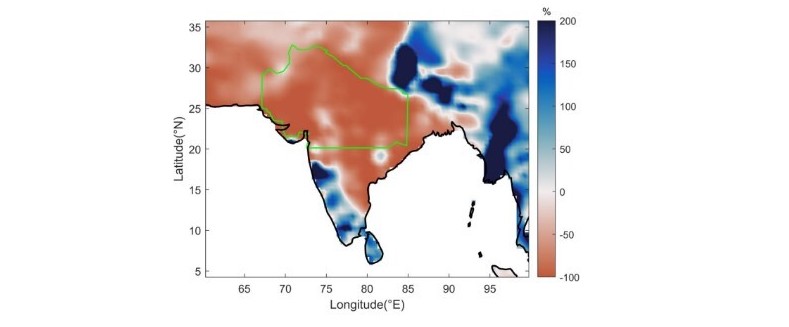

March and April were extremely dry, with 62% and 73.6% less than normal rainfall reported over Pakistan and 71% percent below normal over India in March and 3% in April, making the conditions favourable for local heating from land surface. Persistence of the heatwave since the end of March can thus be partly ascribed to the absence of rain-bearing western disturbances, and partly to the upper atmosphere high pressure resulting in lack of precipitation and subsequent hot weather.

Figure 2: Percentage deviation of precipitation during Mar-Apr 2022 from the 1981-2010 climatology using NOAA Climate Prediction Center (CPC) Global Unified Precipitation data. The study region is highlighted by the green polygon.

Cascading Impacts

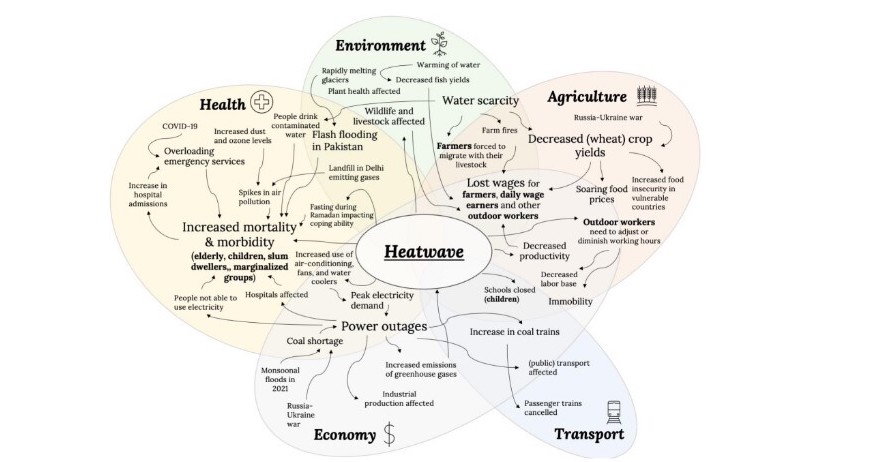

Extreme heatwave conditions have had several macroeconomic repercussions that include productivity loss, suppressed economic outputs that could exacerbate poverty. With the ban on wheat export, India, the world’s second largest exporter of wheat, has lost the chance to capitalise on a tight global market hamstrung by the Russian military operation in Ukraine. Russia and Ukraine happen to be the world’s first and fifth largest exporters of wheat.

The study also states that populations of India and Pakistan are especially vulnerable to extreme heat notably. Around 60 per cent and 40 percent of the workforce in India and Pakistan respectively is dependent on agriculture. The bulk of labour therefore is outdoors, leaving millions of people with the difficult choice of working during periods of dangerous heat or forgoing their livelihoods.

Besides these, the heatwaves have also played a role in triggering secondary events of significant impact. Increased temperatures and evapotranspiration from heatwaves can result in both water shortages and floods from meltwater downstream from glaciated zones. Heatwaves this year resulted in an extreme Glacial Lake Outburst Flood in northern Pakistan and forest fires in India. On April 27th, the Forest Survey of India reported 300 active large forest fires, a third of which were in Uttarakhand province. In Delhi, a massive landfill caught fire for at least 9 days.

Figure 3 : Conceptual map of impact pathways during the heatwave

Farmland devastation

Terminal heatwave did extensive damage to agriculture in parts of South Asia, particularly in north-western India and southern Pakistan, which collectively act as the bread basket of the subcontinent. The arrival of the prolonged and early extreme heatwave coincided with the crucial ripening stages of the wheat growing season. As per report, initial numbers indicate a 20% shortfall in all-India wheat yield this year due to increasing temperatures and heat waves. India was forced into instating a ban on wheat exports from May 13 amid high inflation and the threat looming over domestic food security.

Apart from wheat, other summer crops such as pulses, coarse cereals, oilseeds, vegetables and fruits were also affected. Reportedly, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, and Punjab have estimated a loss of 10-35 percent of crop yields due to the heatwave. With this, local market prices in some regions have witnessed a rise by 15 percent.

In India, a shortage of coal led to power outages that limited access to cooling, compounding health impacts and forcing millions of people to use coping mechanisms such as limiting activity to the early morning and evening.

Energy Crisis:

With extreme heatwave conditions persisting for days together, power demand reached an all-time high of 207 GW and broke the threshold a few times in a matter of days. About 70 percent of India’s electricity generation comes from coal, with about 60 percent of energy provision from coal, oil and natural gas in Pakistan. The ongoing heatwave has already increased the demand for coal imports in India and shortages are resulting in a significant power crunch. At least 16 out of 28 states in India have experienced power outages of between two and ten hours. This makes it even more difficult for people to cope, as even those who have fans or air conditioning may not be able to use them, as well as affecting industry, and agriculture which relies on electricity to irrigate crops for the upcoming paddy growing season.

Way Ahead

Researchers cite the urban poor in India and Pakistan are amongst the most exposed and vulnerable to extreme heat, and are left using coping mechanisms to withstand the extreme heat and earn a daily wage. Rising temperatures from more intense and frequent heat waves will render coping mechanisms inadequate as some regions meet and exceed limits to human survivability. This emphasises the need to record losses and damages occurring due to climate change related disasters. Adaptation to extreme heat though the development of instruments like Heat Action Plans (HAPs) that include early warning and early action, awareness campaigns and behaviour-aligned messaging. Establishing supportive public services is shown to be effective in reducing mortality, and India’s rollout of these has been remarkable, now covering 130 cities and towns.

“There are still large research gaps on adaptation to heat across India and Pakistan that will require study to build a stronger evidence base for action. Heatwaves are disasters, requiring society to tackle issues of people’s vulnerabilities which are underlying causes of disasters. Better urban and health planning, disaster insurances and livelihood protection mechanisms, investment in green spaces, energy grid strengthening, improved water infrastructure and pollution controls could all contribute to ensuring that fewer people suffer as temperatures rise,” said Dr Arpita Mondal, co-author of the study and Associate Professor, Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay.

Heatwave